The Academy was founded by the Academy of Ideas in 2011 and came under the auspices of the Battle of Ideas charity in 2019.

The Academy was founded by the Academy of Ideas in 2011 and came under the auspices of the Battle of Ideas charity in 2019.

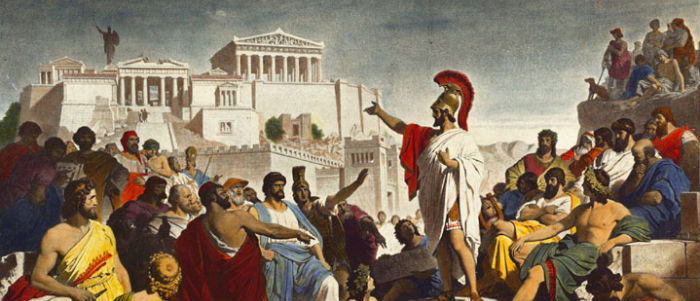

The theme of the eighth Academy – which was held on Saturday 21 and Sunday 22 July – was Popular sovereignty – from Athens to Brexit and beyond and examined the history and significance of popular sovereignty from ancient Athens to the present day. What different forms has society and public life taken from the early appearance of democracy? What have been the trends and challenges? What does contemporary populism and the reaction against it – against national sovereignty and borders – mean for the early 21st century?

PROGRAMME

Day one

Welcome address: On populism

NATION, NATIONALISM AND NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS

(Professor Frank Furedi)

The nation and people’s attachments to this institution continue to be a subject of controversy. Historically, the discussion on the nation focused on attempting to come up with a set of definitions regarding the meaning of a nation and of nationalism. Commentators often distinguished between what they considered to be ‘good’ as opposed to ‘bad’ nationalism. In more recent times this distinction has lost force and all forms of national sentiments appear to come with a health warning. This lecture will call for adopting an approach that situates the discussion on the nation in its different historical context. It will argue that understanding the current debate on the nation requires an understanding of the way in which all forms of pre-political ties and affiliations are depicted and discussed. It will conclude by explaining why national sensibilities and attachments are inseparable from assuming the responsibilities of citizenship.

PEOPLE, NATIONS, AND BORDERS: IMAGINED, INVENTED, OR REAL?

(Angus Kennedy)

The nation according to Benedict Anderson is an ‘imagined community’: he views both nationality and nationalism as cultural artefacts which came spontaneously into existence at the end of the eighteenth century, coterminous with the end of divine monarchy and the dominance of print capitalism. His full definition is that the nation is imagined as limited, as sovereign, and as a horizontally organised community of comradeship. Before modernity borders were porous and religion spoke to universal ends. Since the Enlightenment we live in the divided particularity of national identity. Is his thesis correct? Are nations and borders simply inventions of modernity or should we also take account of what Anthony Smith calls the ‘deep roots of nations and nationalisms in an “ethnic” substratum’? In the cultural history of a people in other words?

THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE CONCEPT OF POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY IN EARLY-MODERN EUROPE

(Dr Rachel Hammersley)

Popular sovereignty lies at the heart of our modern understanding of democracy government. But what does this concept mean and how did it emerge? In the large states of Northern Europe, for much of the medieval period and beyond, the term ‘sovereign’ was conventionally used to describe a monarch. Yet, from the sixteenth century onwards, the concept was being transformed. This lecture will trace that transformation, taking in the influential distinction drawn by Jean Bodin between sovereignty and government and the practical and theoretical developments arising out of the English, American and French Revolutions.

THE IDEAL OF THE LIBERAL NATION-STATE

(Dr Jim Panton)

Liberalism is generally, and many liberals are in particular, ambivalent about nationalism. On the one hand, early liberal and republican thinkers developed bold attempts to theorise sovereignty as the foundation of state legitimacy and unifying condition of the nation. On the other hand, liberal thinkers have struggled to justify the accidental character of national boundaries and the implications these have for inhabitants of different nations. Further, modern liberals disavow the chauvinism they believe to be inherent in nationalism, proposing instead a cosmopolitan ethics. This lecture will consider the development of the liberal ideal of the state in the thought of Locke, Rousseau, and ultimately, Kant, and look at the extent to which the Kantian model of sovereignty as the foundation of nation-statehood is increasingly maligned.

COLONIALISM AND EMPIRE

(James Heartfield)

Must Rhodes Fall? The debate over colonialism seems even more contested today than it was when European powers had colonies all over the world. The protests over the statues of Cecil Rhodes in Cape Town and Oxford University, and other monuments to colonial or slave era public figures have all underscored a growing unease about Britain’s colonial past. The intellectual programme of ‘decolonising the curriculum’ at SOAS and other universities has been met with positive acquiescence from college authorities. Historical interest in the colonial era is strong, encouraging a lot of good research in specific studies; at the same time the intellectual framework in which Empire and the colonies are understood suffers from a moralistic and near ahistorical approach as the backlash to Professor Nigel Biggar’s ‘Ethics and Empire’ project at Oxford University has demonstrated. How can we understand the historical debate today, and what are its practical consequences for the present?

NATIONALISM: THE UNACCEPTABLE FACE OF IDENTITY POLITICS?

(Tim Black)

Critics of nationalism seem to find merely invoking the Nazi rhetoric of blood and soil is enough to condemn all forms of nationalism, and not just the socio-biological babble of the National Socialists themselves. In doing so, what might be specific about this ethnic or racial form of nationalism – the Eastern, or bad form of nationalism, as Hans Kohn had it – tends to be missed. This lecture will explore the specificity of this ‘bad nationalism’, from its roots in the German Romantics’ reaction to the perceived privations of modernity and the Enlightenment, through to its brutal climax in the 20th century. It will then explore the mutation and subterranean existence of this ‘bad nationalism’, and ask whether it is both the original form of identity politics, and now its most unacceptable face.

Day two

GLOBALISM AND NEO-LIBERALISM

(Phil Mullan)

Globalists see themselves as the peacekeepers through their advocacy of the values of liberalism, free trade, democracy and internationalism. Yet the actions of the institutions over which they preside seem to bring the opposite. They generate division and conflict both within nations and also between them. So we have heightened polarisation within Brexit Britain, as well as within other leading European countries. Within the European Union, tensions have escalated both between north and south, and between west and east. And despite the claimed Macron-Trump bromance, trans-Atlantic conflicts are mounting too. Is all this an inevitable outcome of the globalist perspective that denies the effectiveness of national state policies? Is there a solution to the widely held ‘global trilemma’, suggested by the writer Dani Rodrik? This says that economic globalisation, democracy and national sovereignty are mutually incompatible: we can combine any two of the three, but never have all three simultaneously and in full.

ENVIRONMENTALISM AND DEMOCRACY

(Josie Appleton)

Ours is not the first age to conceive of national politics in terms of ideas of nature. Yet the idea of anthropogenic climate change marks a new development – where environmentalism no longer reflects a national spirit, but rather seeks to negate or restrict it. This lecture will look at the history of nature in politics, and show how the politics of climate change represents a break with this past.

DEMOCRACY: A HISTORY OF AN IDEA

(Paul Cartledge)

From 500BC until 320BC, a radically democratic republic, which gave unprecedented weight to the decisions of ordinary men, flourished in the city state of Athens. Rarely have the people been as powerful as they were during this bright, brief bloom of *demokratia*. Yet its legacy is far from certain. For centuries, it was known through the eyes mainly of its critics, rather than its supporters. And later republican revivals during the Renaissance and the English Civil War drew on Rome rather than Athens. So what has been the Athenian legacy? What made its theory and practice of democracy so remarkable? And in the light now potentially cast by what we now know of the Athenian democratic ideal, how should we view democracy in the West today? Does it live up to its Ancient antecedent? Or does it fall short?’

Short lectures

- ON HABERMAS (Patrik Schumacher)

- IMMIGRANT VERSUS CITIZEN: IS FREEDOM OF MOVEMENT A HUMAN RIGHT? (Jon Holbrook)

- 100 YEARS OF SUFFRAGE (Joanna Williams)

A LIBERAL DEFENCE OF POPULAR SOVEREIGNTY

(Professor Frank Furedi)

This lecture will examine why liberals have throughout history been suspicious of popular sovereignty. The liberal critique of popular sovereignty is frequently motivated by its fear of democracy, public opinion, and mass politics. In recent times anxiety about the rise of so-called populist movements has led to the re-emergence of the classical liberal dread of popular sovereignty. The lecture will argue that liberalism need not fear popular sovereignty. It suggests that popular sovereignty and democracy constitutes a solid foundation for liberty and freedom. The exercise of popular sovereignty educates the public in the virtues of freedom and liberty and prepares people to play the role of citizens.